Java Reminders

Some reminders when working with Java…if that is what you want to call them.

Math.abs() can return a negative value.

jshell> Math.abs(Integer.MIN_VALUE)

$1 ==> -2147483648

jshell> Math.abs(Integer.MIN_VALUE + 1)

$2 ==> 2147483647

The highest value a 32 bit integer can contain is +2147483647. Attempting to represent +2147483648 in a 32 bit int

will effectively roll over to -2147483648. When using signed integers, the two’s complement binary representations

of +2147483648 and -2147483648 are identical. This is not a problem, however, as +2147483648 is considered out of

range.

Use compareTo() over subtraction pattern.

public class Testing {

public static void main(String[] args) {

final BankAccount accountOne = new BankAccount(1_073_741_825);

final BankAccount accountTwo = new BankAccount(-1_073_741_823);

final int comparison = accountOne.compareTo(accountTwo);

System.out.println(comparison); // -2147483648

}

private record BankAccount(int balance) {

public int compareTo(BankAccount anotherAccount) {

return this.balance - anotherAccount.balance;

}

}

}

Subtracting a negative number from a positive number is addition. The comparison value 2147483648 is too large for

an int and rolls over to -2147483648.

public class Testing {

public static void main(String[] args) {

final BankAccount accountOne = new BankAccount(1_073_741_825);

final BankAccount accountTwo = new BankAccount(-1_073_741_823);

final int comparison = accountOne.compareTo(accountTwo);

System.out.println(comparison); // 1

}

private record BankAccount(int balance) {

public int compareTo(BankAccount anotherAccount) {

return Integer.compare(this.balance, anotherAccount.balance);

}

}

}

Comparison value is 1.

Floating Point Numbers

It’s 2022 and you are using floating point numbers. You can add a positive number to 1 and get a value less than 1.

jshell> DoubleStream.of(1.0, 1e-16).sum();

$2 ==> 0.9999999999999999

jshell> DoubleStream.of(1.0, 1e-16).reduce(0, Double::sum);

$3 ==> 1.0

DoubleStream double sum();

Returns the sum of elements in this stream. Summation is a special case of a reduction. If floating-point summation were exact, this method would be equivalent to: return reduce(0, Double::sum); However, since floating-point summation is not exact, the above code is not necessarily equivalent to the summation computation done by this method. The value of a floating-point sum is a function both of the input values as well as the order of addition operations. The order of addition operations of this method is intentionally not defined to allow for implementation flexibility to improve the speed and accuracy of the computed result. In particular, this method may be implemented using compensated summation or other technique to reduce the error bound in the numerical sum compared to a simple summation of double values. Because of the unspecified order of operations and the possibility of using differing summation schemes, the output of this method may vary on the same input elements.

Floating point addition is not commutative and I assume this is based on the Kahan sum implementation.

Remember, decimal literals are of type double and need to be cast down to float.

final float error = 0.0; // compile error

final float error = 0.0F;

But an int literal is only of type long if it ends with an L.

final long sum = 0L;

It needs to be cast up to a long. Not the consistency we would expect.

Zero

Lets not forget about +0 and -0. The IEEE-754 standard

has two zeros. When you divide by each one, you get a different result.

System.out.println(1.0 / 0.0); // Infinity

System.out.println(1.0 / -0.0); // -Infinity

But…

System.out.println(-0.0 == 0.0); // true

…even though -0.0 and 0.0 hava different bit patterns. Care must be taken when implementing the absolute

value of a number.

Modular arithmetic

I’ve been burned by this a lot. I enjoy Project Euler,

Rosalind and Advent of Code. When I think of

modulus, I think in terms of remainder classes. For any modulus n, there exists n - 1 remainder classes denoted as the

least residue system modulo n. The set of integers

{0, 1, 2, ... , n − 1} less than n from

Euclidean division.

Given two integers a and b, with b ≠ 0, there exist unique integers q and r such that

a = bq + r

and

0 ≤ r < |b|

In Java, the % is the remainder operator and Math.floorMod() is the modulo operator which is consistent with

the Euclidean definition where the remainder is always non-negative, 0 ≤ r, and is thus consistent with the

Euclidean division algorithm. Each language may have a different

definition of this operation.

System.out.println(-18 % 5); // -3

System.out.println(Math.floorMod(-18, 5)); // 2

URL class

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException, MalformedURLException {

final Set<URL> domains = new HashSet<>();

domains.add(new URL("https://www.google.com/"));

System.out.println(domains.contains(new URL("https://www.google.com/"))); // true

// Wait 5 minutes

Thread.sleep(300_000);

System.out.println(domains.contains(new URL("https://www.google.com/"))); // false

}

Java resolves domain names in URLs into IP addresses before generating hash codes for them. If you wait 5 minutes,

Google will load balance to a new IP address, and any new URLs you construct will have different hash codes.

This is well documented but serves as a reminder.

Boxed Types

Just a reminder when using boxed types…

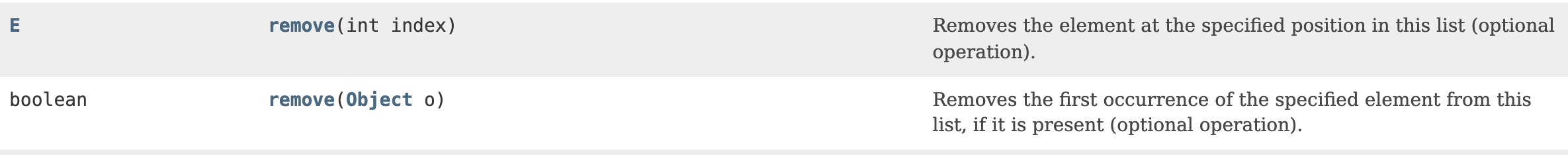

List interface

final List<Integer> list = new ArrayList<Integer>(Arrays.asList(1,2,3));

final int first = 1;

list.remove(first);

System.out.println(list);

[1, 3]

final List<Integer> list = new ArrayList<Integer>(Arrays.asList(1,2,3));

final Integer first = 1;

list.remove(first);

System.out.println(list);

[2, 3]

Collections only use boxed (object) types but it’s not common to use a boxed type otherwise unless you are

expecting a null or Optional check. Just a reminder…

final int a = 1000;

final int b = 1000;

System.out.println(a == b); // true

final Integer c = 128;

final Integer d = 128;

System.out.println(c == d); // false

final Integer e = 127;

final Integer f = 127;

System.out.println(e == f); // true

final Integer g = 1000;

System.out.println(a == g); // true: g is unboxed to a primitive.

If the value p being boxed is an integer literal of type int between -128 and 127 inclusive (§3.10.1), or the boolean literal true or false (§3.10.3), or a character literal between ‘\u0000’ and ‘\u007f’ inclusive (§3.10.4), then let a and b be the results of any two boxing conversions of p. It is always the case that a == b.

But -128 < 10 < 127.

final Integer m = 10;

final Integer n = 10;

System.out.println(m == n); // true

final Integer x = new Integer(10);

final Integer y = new Integer(10);

System.out.println(x == y); // false

Integer(int) can be fooled but it is deprecated and marked for removal.

Remember, use if (x.intValue() == y.intValue()) or if (x.equals(y)).

StringBuilder

Remember…

final StringBuilder stringBuilder = new StringBuilder('[');

does not add a [ to the beginning as intended. The char passed in has it’s int value 91 used as the initial

capacity of the StringBuilder object.

String

You can say that format string vulnerabilities are not a thing in Java, but String.format("%2147483647%") is not

your friend. It tries to create a String of length Integer.MAX_VALUE, that is 2GB. To make it succeed

(assuming your heap size is big enough), pick a slightly smaller size.

Remember, String literals get interned.

final String s1 = "hello";

final String s2 = new String("hello").intern();

System.out.println(s1 == s2); // true

final String s1 = "hello";

final String s2 = new String("hello");

System.out.println(s1 == s2); // false

…but don’t confuse reference comparison with content comparison. Use s1.equals(s2).

Remember, as with any programing language or tool, just because you can doesn’t mean you should.